Sailing

About

Sailing allows participants to enjoy the freedom of movement and independence – whether it’s a lazy afternoon on an inland lake, mastering the wind in recreational races, or challenging yourself with elite-level competition, sailing offers something for everyone.

Individuals of all abilities can enjoy the sport of sailing as boats can be adapted for seating, controls and rigging. The first step is getting yourself to a sailing center that has an adaptive program and joining the fun. There is no limit to finding out how far you can go.

Sue Beatty, former Executive Director of Chesapeake Region Accessible Boating (CRAB) in Annapolis, Maryland, a Move United Chapter, recommends starting with a short classroom session, especially for those who are completely new to sailing. “We cover a basic set of terms for parts of the boat such as main, jib, rudder, keel, etc. We also cover the very basic principles of sailing – how the sail is like a wing, how sails are “trimmed” or adjusted depending on the wind and direction of sail, and how the keel works to keep the boat upright. Finally we discuss (and stress) safety and the rules of the road.

“After covering the basics we get people out on a boat with an experienced skipper. Seeing, touching and feeling are the best ways to make those abstract basic concepts clear. Our skippers let people take the helm and handle the sails, but are always right there to step in and keep things safe. From there it’s just more sailing and chances to learn and try things,” Beatty said.

Some individuals with physical disabilities will need assistance to transfer into and out of a boat. There are a variety of ways to do so, including use of mechanical lifts, transfer boarding benches, and personal assistance. In all cases, the boat is securely attached to the dock for safety.

“Paraplegics are routinely able to sail the boats once they’ve been assisted aboard,” said Beatty. “Our staff and volunteers assist guests on and off of the boat. That’s where those open and broad decks come in handy. Additionally we use floating docks and tie the boats up very tight when boarding or disembarking so the height of the boat’s sides don’t vary and the boat doesn’t move very much. We also have a special seat to board guests who are not ambulatory. It’s a metal box with a hinged extension that unfolds and can be positioned like a ramp into the boat. There are stainless steel hand guards on the side. Someone in a wheelchair can park it next to the seat and with assistance or without, shift themselves over to the seat. They then slide down the ramp (not at all steep) until they are next to the boat seat. There they shift again into the seat. We always have people there to assist as necessary with the process. And it is reversed for disembarking.”

Freedom 20s are sailed by CRAB. These boats begin with a design that is very forgiving and easy to access. They have a carbon fiber mast that does not need stays (the wires that hold up the mast on most boats). That, combined with broad, flat decks makes it easy to get on and off of the boat for one or more people. The boats have a large, heavy keel which makes them very stable and nearly impossible to capsize.

The boats have two fiberglass seats. Each seat is a single molded seat and back with two seat belts to safely secure sailors in them. Each seat is mounted on an aluminum bar that allows it to pivot from one side of the boat to the other if desired. Normally they are locked in on one side or the other. There is a small footrest on the support bar as well. Someone who is strapped into one of these seats is both comfortable and very secure.

The Freedom 20s have a “self tending” jib which means it tacks from side to side without needing much attention. All of the ropes (“lines”) are lead in a clever way to both sides of the cabin top, where the forward crew member can access them from his or her seat. The line that controls the main sail is also cleverly configured so that it can be controlled from either the front or rear seat. Tiller extensions are utilized by the helmsperson while driving the boat for better control of the tiller (the control for the rudder and therefore direction of the boat). Altogether two people with disabilities can manage every aspect of sailing the boat.

Bob Ewing is president of Footloose Sailing Association, a Move United chapter located in Seattle, Washington.

“Adaptations for disabilities include things like special seating, electric power winches, electric starter motors, talking GPS, roller furling, davit transfer systems (similar to Hoyer), joy stick controls and other innovations sometimes specific to a certain situation,” Ewing said. “For example we have two 16-foot boats that have electric winches for steering and sail control set up to work with a joy stick, chin stick or sip and puff. Once we give the sailor the basic knowledge, they can have control of sailing a boat. If you think about that and the situation that the sailor lives in, it becomes very powerful.”

Footloose has both big and small non-athletic sailboats available for sailing experiences. “A person learns about sailing by going sailing, talking about sailing and reading about it. It can be done in structured lessons or over time at your own pace,” Ewing said. “There are people who just go for a sailboat ride. It’s recreation, leaving your disability at the dock and getting out on the water with your friends. Because of disability or mind set, they want to help on the boat, but not have the responsibility of skippering the boat. So there’s your crew who will pick up sailing knowledge at their own pace and ability,” Ewing said.

“Others decide that they want to learn everything about sailing and pursue that. The best example is a high quad in Chicago who races in the Chicago to Mackinac race on Lake Michigan, sits in a special seat in the stern of his boat and calls the tactics, sail set and all the decisions for racing his boat. You need the mind, the knowledge and the ability to communicate to be a skipper,” he said.

Equipment

Sailors with mobility impairments who may need something to hold onto for balance when crossing the boat can use a simple a thwartship (from one side to the other at right angles to the keel) grab bar when sailing. Others whose disabilities prevent them from standing can use a simple transfer bench. Sometimes the transfer bench is used in conjunction with a grab bar to cross the boat. Another option to help slide across the boat is a line at least one-half inch in diameter tied from rail to rail. For an individual who cannot hold themselves upright, straps or harnesses can secure the sail to the seat. For those with stability issues, a seat that provides trunk or back support such as one with a high-backed molded seat, suction handles, grab bars, lateral supports or a good harness can be used. Other seating adaptations can include padding, lap and/or chest belts, and seats modified from wheelchair bases, boat seats, and golf cart seats. Lack or limitation of hand function can be addressed with electronically-assisted steering and sheet trimming. Systems include 4-way joysticks which can be used with foot/toes or hand/fingers, or chin-control.

For those with severe quadriplegia, sip and puff control allows them to use a straw-like mechanism to control sail movement by how they blow, sip, or bite the control. These and other adaptations are explained in the US Sailing’s Adaptive Sailing Resource Manual.

Click here for a list of equipment resources.

Competition

Everhart Skeels enjoys not only the freedom sailing involves, but the strategy in competition.

“I have always been a competitive athlete and I enjoy that aspect of sailing. It’s not about who is the strongest, but who can think the best. It’s a three dimensional game of chess that is going on and the chess board is always changing. Water is never the same because of currents and the wind is sometimes up and sometimes down. Sailing is being attuned to what is going on around you to make your boat fastest.

“My favorite saying and its very similar to life: you can’t change the wind but you can always adjust your sails,” she said. “Life is like that and I especially think that life can be like that if you are someone like me who has acquired a disability. I have had to learn how to change myself many times, but still keep going forward. I like that aspect. You can always make it work. You just have to figure out a way.”

Recruiting Sailors for the Paralympics

To identify sailors that have the potential to be elite National Team players and possibly Paralympians, Alison keeps in contact with various adaptive sailing programs nationwide, and consults with local and regional coaches. She also networks with college coaches who may know of athletes within their schools who are disabled.

“We look for athletic and competitive-minded people,” Alison said. “There is no established pathway directly into competitive disabled sailing like the Olympic program has with the junior sailing programs that are direct feeds, so we look at open sailing arenas to identify sailors who may have disabilities. One of my Paralympians, who lost his leg to cancer at age 8, never considered himself disabled. I recruited him when he was doing an Olympic program.”

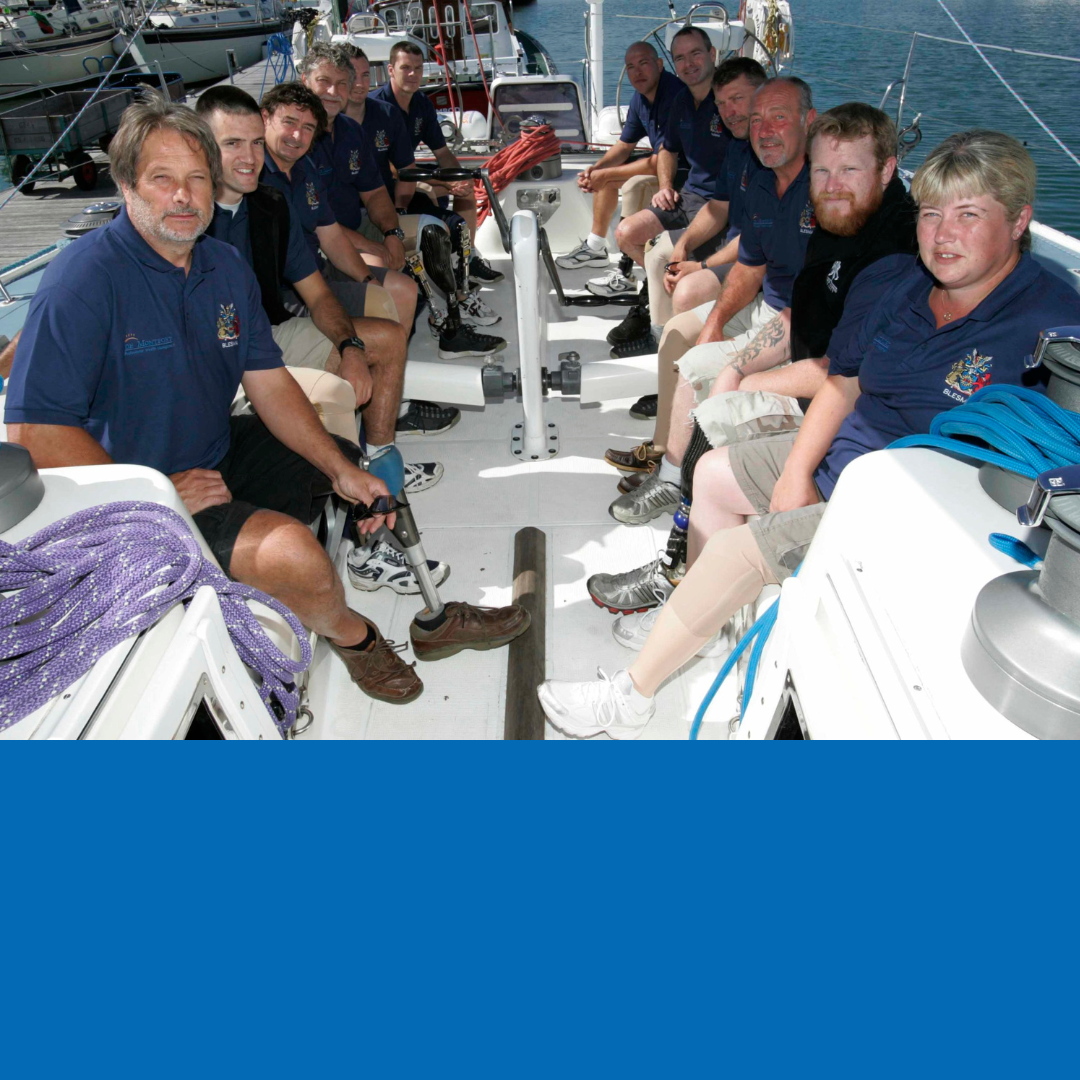

“The other avenue we are looking at to open up a direct pathway is through the military. This year, we are partnering through a grant made available from the VA and the USOC, allowing us to do a series of learn to race boot camps to expose our injured warriors to the sport of sailing. It’s in its infancy stage, but it’s been very well received so far and I think it holds a lot of potential.”

Paralympic Level Sailing

There are three medal events at the Games. These are the 2.4mR, SKUD 18 and Sonar classes, featuring one, two and three sailors per boat respectively. Each event consists of a series of up to 11 races – weather permitting. Sailors accumulate points according to their positions after each race, with one point for first, two for second and so on. At the end of racing, all the points except the worst score from each team are added together. The winner is the sailor or team with the lowest points total at the end of the races.

“With those three classes, we start doing more specific training through nationally-organized training camps,” Alison said. “Training sessions consist of land-based education followed by practice in the water, then a critiquing session. Some camps are boat handling-oriented where we will be working on the functional sailing of the boat, coordinated crew work, and moves within the boat and around the race course. Other camps we work on speed testing – equipment-related, sail-related, or rig tuning. In some training camps, we are working strictly on tactics and strategy. Depending on what point we are in the year or what competitions are leading into an event, we plan our training around what we are trying to accomplish.

“For example, the week before a world championship, we would do training on site at the World Championship site and focus on fine-tuning starting strategies and set up. Whereas six months prior, we would do a camp working on speed, speed set up through sail trim, sail shape and sail trim,” she said. “Depending on where the groups of athletes we are working with are in their development, each athlete or team might have specific aspects of their own sailing that they are working on within the bigger scope of the camp.”

Event Qualifiers

To be eligible for the Paralympic Games, there are qualifying events open to any aspiring athlete who is classified. For the 2016 Paralympic teams, there were two qualifying events: the 2014 IFDS Sailing World Championships and the 2015 IFDS Sailing World Championships. The results from those two events combined determined who went to the Paralympics.

There will be no qualifiers for the 2020 Tokyo Paralympic Games, as it was not approved by the IPC for the upcoming Olympics.

Paralympic Classification

The Paralympic sailing classification system is based on three factors – stability, hand function, and mobility. Vision impairments have a separate classification procedure. After the evaluation by the Classification Committee, sailors are awarded points, based on their functional abilities, ranging from one to seven, starting from 1 for the lowest and 7 for the highest level of functionality.

Each boat (single, two person, and three person) uses its own classification point system to make up a team. In the single-person boat, each sailor has to meet a minimum criteria, which is having any classification rating from 1-7. The two-person boat requires one sailor to be rated a 1 or 2 with the crew having any classification rating (1-7), but at least one of the two sailors must be female. In the three-person boat, to make sure that no crew has an advantage or disadvantage in the competition due to impairment, each team of sailors is allowed a maximum of 14 points. For example, a sailor with complete quadriplegia (1 rating) is likely to compete with a teammate who may have a single, above-knee amputation (7) and another teammate who is missing a hand (6 rating) for a total of 14 points.

Athletes with vision impairment are placed into one of three competition rating classes, based on their visual acuity and field of vision.

Depending on their visual ability, they compete in sport class 3, 5 or 7, with 7 indicating the highest eligible visual ability.

In a single-person keelboat (2.4mR) all sailors are required to have a minimal disability or a higher level of disability.

In a two-person keelboat (SKUD 18), the crew includes one female and one severely disabled sailor with a one point classification.

In a three-person keelboat (sonar), the total crew points do not exceed 14.

“We have a lot of quads driving boats, so there is quite a range of disabilities,” Alison said. “In contrast to many of the sports, the amputees don’t just play with the amputees, the blind don’t just play with the blind, the quads don’t play with the quads. Everybody is combined in the sport of sailing.”

Getting Classification

When a sailor is classified, it’s for a four-year Olympic cycle (quadrennium).

“There is also a list of all the sailors who have been classified for this quad on the US Sailing website, including their classification rating,” Alison explained. “For example, if I was a sonar sailor and I classified as a three and I was looking for teammates to sail with, I could go to the classification list and see who I might be compatible with. Sometimes we as coaches suggest to people who they should sail with. Other times, the sailor will read the system and try to pair up with a geographically compatible teammate to practice with.

Learn More

“As you get better and better and you want to pursue that Paralympic dream, then the urgency for owning your own equipment becomes greater,” Alison said. “If you are an elite athlete you want to invest in your own equipment. It’s like with wheelchair racing, sled hockey, or sit-skiing, you want your own chair/sled/ski because it fits you best and it has adaptations that make it better for you. The same thing is true at the elite level of Paralympic sailing.

“Sailing is not the most inexpensive sport once you own equipment and take into consideration travel and training. However, on a national team, although we don’t have monthly stipends, sailors do get some grant funding and we provide a lot in terms of resources and support for logistics, coaching, shipping and transportation. We do what we can within our funding and our budget to be able to help our athletes. We also advise them on creating personal websites and how to go about fundraising on their own – and they are pretty successful at it.

Program Near You

Ready to try out sailing? Click here to find a location near you!